Philadelphia’s City Hall commands attention. Placed at the crossroads of Broad and Market Streets, it serves as an architectural compass, dividing the City into north, south, east, and west. Walking through its monumental archways inspires awe. Driving around it requires Indie 500 skills. No other American city has such a colossal building that, literally, stops traffic. How did it come to be? Read on to find out!

City Hall History

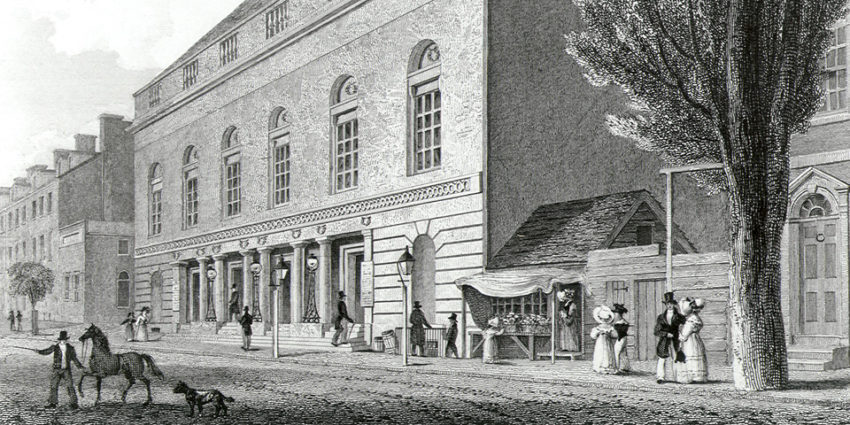

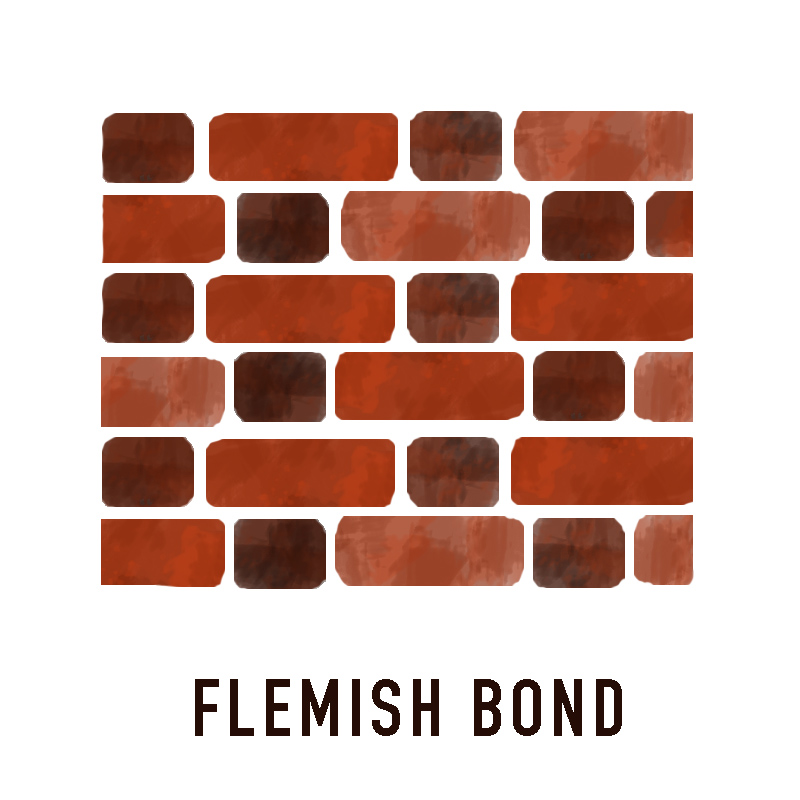

Philly’s first City Hall was built during the time of William Penn and was located on 2nd Street. Its ground floor served as a jail. In 1791, the second City Hall, now known as Old City Hall, opened in a Federal-style red brick building, which still stands today adjacent to Independence Hall. During the 1790s, it served as the US. Supreme Court and is open to the public today.

Image: Antoine Taveneaux via Wikimedia Commons.

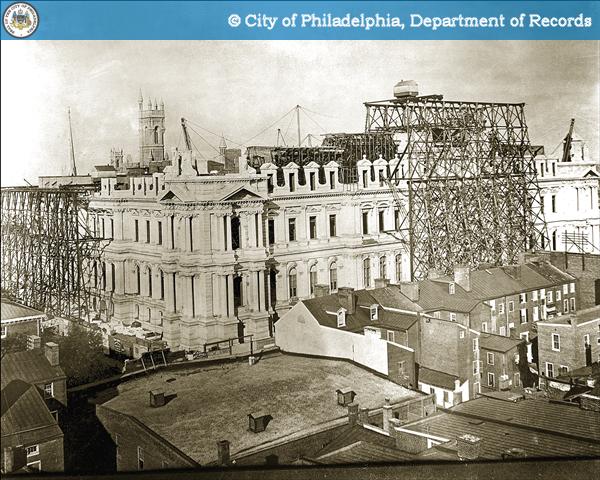

As the City grew, so did its ambition. In 1870, voters selected City Hall’s current site at what is now Dilworth Plaza (formerly Penn Square) for what would be the largest City Hall in the nation. Designed in the Second-Empire Mode of French Renaissance Revival architectural style by architect John McArthur, Jr., construction began in 1872.

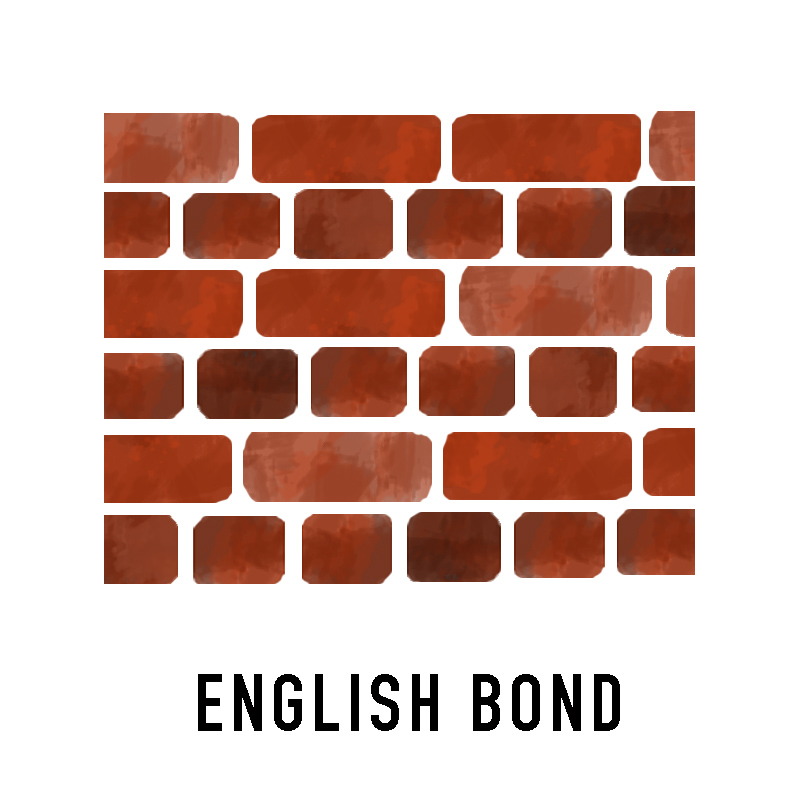

Completed in 1901, Philadelphia’s current City Hall is an iconic building but it was also an engineering feat. A 2006 brass plaque at its base from the American Society of Civil Engineers states, “The building is still the world’s tallest masonry load-bearing structure made of 88 million bricks and thousands of tons of stone…it is the nation’s most elaborate seat of municipal government.”

City Hall Architecture and Sculptures

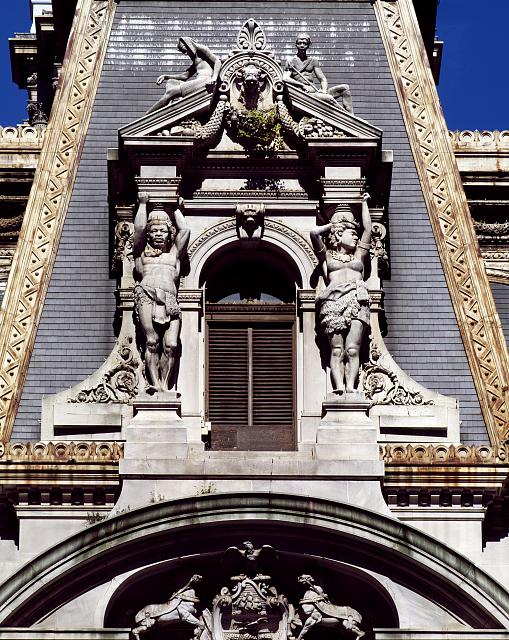

The walls are brick, faced with white marble, and the seven-story building measures 486 feet by 470 feet. The Tacony Iron and Metal Company hired civil engineer C.R. Grimm to design the upper wrought-iron frame, metal-clad portion of the tower, which surmounted the masonry tower and supported the 37-foot-tall, 27-ton bronze statue of William Penn. Sculptor Alexander Milne Calder designed the 37-foot high, 27-ton bronze statue, cast in fourteen sections at Tacony Iron and Metal Company. It took two years to complete and was installed in 1894.

At one time, every eighth grader in the City was taken to the top of William Penn’s hat for a spectacular view of the City. The creation of an observation deck below Penn’s feet brought the view down to 548 feet, but it is currently closed due to the pandemic but tours of City Hall are still available at the Love Park Visitor Center kiosk.

Did you know William Penn is not alone up there? Take a close look and you’ll find 250 sculptures of nature, artists, educators, and engineers who embodied American ideals, including several sculptures of the building’s designer McArthur and two Native Americans. BillyPenn.com has a guide to all 250 sculptures, including bison and cats.

Preservation & Restoration

Did you know our iconic City Hall building was almost demolished? In the mid-1950s, the city considered demolishing the building and erecting a new one elsewhere. According to an article in the New York Times, “calls for the demolition of City Hall began when it was less than 20 years old and persisted for decades.”

At the time, Edmund Bacon was the Executive Director of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission, and renowned architect Louis I. Kahn was the master planning consultant. Both advocated for demolishing the building due to the building’s disruption of traffic as well as its Second Empire architectural style, which had already fallen out of fashion by the time it was built. Louis I. Kahn called it “the most disreputable and disrespected building in Philadelphia.”

In a victory for historic preservation, the building was saved and remains today, not because of public outcry but because cost estimates to demolish it came in equal to the cost of construction. The high cost of removing it and objections from members of the American Institute of Architects caused the city to acquiesce.

As early as 1910, City Hall Tower was covered in a layer of black soot, due to coal being the primary source of power in the city. The soot was not removed until the 1960s and again in the 1980s during a restoration project that lasted more than 5 years. Yimby provides is a closer look at the restoration that took place in the 1980s.

Dilworth Park: The Heart Of The City

Surrounding City Hall is Dilworth Park. In 2014, Dilworth Plaza, named for Mayor Richardson Dilworth (1956-1962), originally designed in 1972, was totally redesigned and renamed Dilworth Park. This transformation turned an under-utilized and unsafe area into a brightly lit recreational center currently featuring the Rothman Orthopedics Ice Rink, the Deck the Hall Light Show and it recently hosted the Made in Philadelphia Holiday Market.

In the spring, Dilworth Park hosts fitness classes, roller skating specials, and performances from some of Philadelphia’s many arts and cultural organizations. A beautifully appointed park with an interactive fountain, lawn, and tree grove seating areas, it features a café. Festivals live musical performances, outdoor movie screenings, and happy hour specials bring an audience to the park at all hours of the day and night. All of this takes place above a major transit hub and under the watchful eyes of our City’s founder, William Penn.

This article is part of a series titled “The Secret Life of Buildings” where we cover the history and architecture behind Philadelphia’s storied buildings. We’ve written about row house styles, courtyards, and star bolts, among other topics. What else would you like to learn about? Follow us and DM us on Facebook or Instagram to let us know!