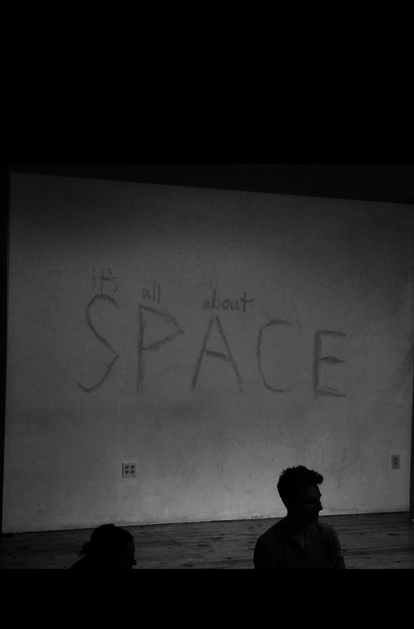

Niki Cousineau approaches real estate the same way she approaches her practice as a dancer and choreographer – it’s all about space. Niki, a new agent wi th Solo, appreciates space in all of its forms. She brings this appreciation to her work as a realtor. Who better to help you find your next home than someone who sees the beauty in a whole range of unique spaces?

th Solo, appreciates space in all of its forms. She brings this appreciation to her work as a realtor. Who better to help you find your next home than someone who sees the beauty in a whole range of unique spaces?

While the connection between dance and real estate might not be readily apparent, a deep emphasis on the spaces we inhabit is something shared by both. Recently Niki took us on a tour of some remarkable arts and performance spaces that most Philadelphians might not have access to normally. Take a look at our insider’s peek at Philly’s cool performance, arts, and practice spaces!

The Glass Factory

The first place Niki showed us is tucked away on a quiet side street in Brewerytown. From the outside you would never guess the amazing, cavernous space that lies within. Niki first discovered this space with the company she co-directs, Subcircle. Subcircle came to the Glass Factory with their show Hold Still while I figure this out in June 2016. That piece was more recently performed at FringeArts this past fall.

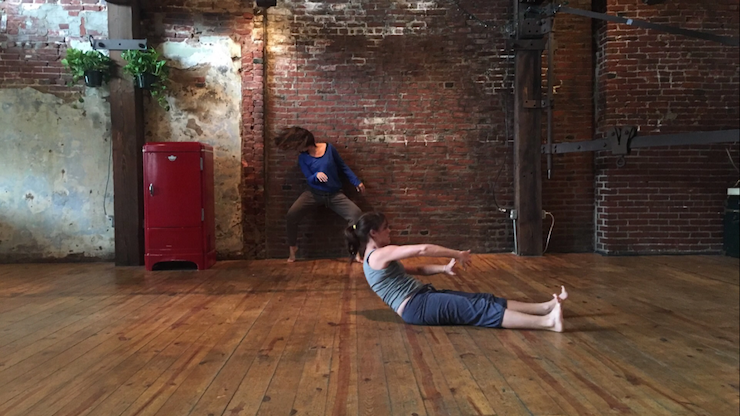

One thing that really stands out in the Glass Factory are the raw materials. While the space is simple, the signs of it’s past life as an auto shop give off a raw, edgy vibe. The exposed brick with phrases such as “Cars Washed” and “Brakes” painted on and the iron beams fit in with today’s popular post-industrial vibe. Meanwhile, the spacious stage and skylights add lightness and grace to the room.

While Niki discovered the Glass Factory through her dance and choreography work, the space hosts a wide array of events including music performances, martial arts classes, and art installations.

MAAS Building

The second location that Niki gave us a behind-the-scenes glimpse of was the MAAS Building. This brewery turned trolley repair shop in Olde Kensington is, coincidentally, just two doors down from our project Kensington Yards. Now the building is home to two offices on the ground floor, an events and practice space, a recording studio, a large garden courtyard behind the main building, and a private residence.

When owners Ben and Catherine first acquired the MAAS, it hadn’t been used since its days as a trolley shop. It’s because of this that so much of the original industrial workshop character is preserved. A floor was built to divide the building into two stories, and this diverse practice, performance, work, and home space was born.

While one of the most common uses of the upstairs space is actually weddings, Niki and her company Subcircle host their works in progress series and rehearse there. Other local groups that take advantage of this gorgeous, open space are Almanac Dance Circus Theatre and New Paradise Laboratories.

Crane Arts

The last space Niki showed us was Crane Arts. Crane Arts is a well established place for artists’ studios and rental space in Olde Kensington. In more recent years they transitioned their Icebox Project Space to having a more structured public presence as well. The Icebo x already existed as rental space in the Crane Arts building, in fact, Subcircle did their piece Still Unknown there in 2006. Now they host more regular performances, installations, and shows. With this expanded programming, Crane Arts moves beyond its role as a rental space. The directors are interested in expanding their scope and joining the conversation in Philly’s art community.

x already existed as rental space in the Crane Arts building, in fact, Subcircle did their piece Still Unknown there in 2006. Now they host more regular performances, installations, and shows. With this expanded programming, Crane Arts moves beyond its role as a rental space. The directors are interested in expanding their scope and joining the conversation in Philly’s art community.

Believe it or not, the Crane Arts building used to be a plumbing warehouse. After that a seafood packaging plant called the enormous building home. Between the shuttering of that business and its 2004 purchase, the building remained vacant. The Icebox, which we spent most of our visit in, was actually a giant walk-in freezer back in the days of the packaging plant, hence its name. Some of that original character is still noticeable in the large, blank space suitable for all sorts of performances and installations.