Philadelphians love the row house as much as they love their cheesesteaks and water ice. How did this unique architectural style take root and thrive for over 300 years? We will take a look at the origins and evolution of the row house, from a working man’s home to an opulent mansion.

While the row house is synonymous with our City, we did not originate the style. We borrowed it from London and Paris where it first appeared in the 16th century. (Next time you are in Paris, check out the swank Place des Voges. It looks like a mansion, but is actually a series of row houses.) In London, row houses were built for both workers and noblemen. Philly took that cue and ran with it.

From humble dwelling to stately splendor

Early row houses, dubbed Bandbox or Trinity, were only 400-600 sq ft. They had one entry, one room on each floor, a narrow winding staircase, and no running water. Toilets? Outside! They first appeared along narrow alley blocks near the waterfront in the early 18th Century to house dock workers. Trinity houses can be found today in Society Hill, Washington Square West, Queen Village, Old City, and Kensington. Want to learn more about trinity homes? We covered them in another blog post from this series.

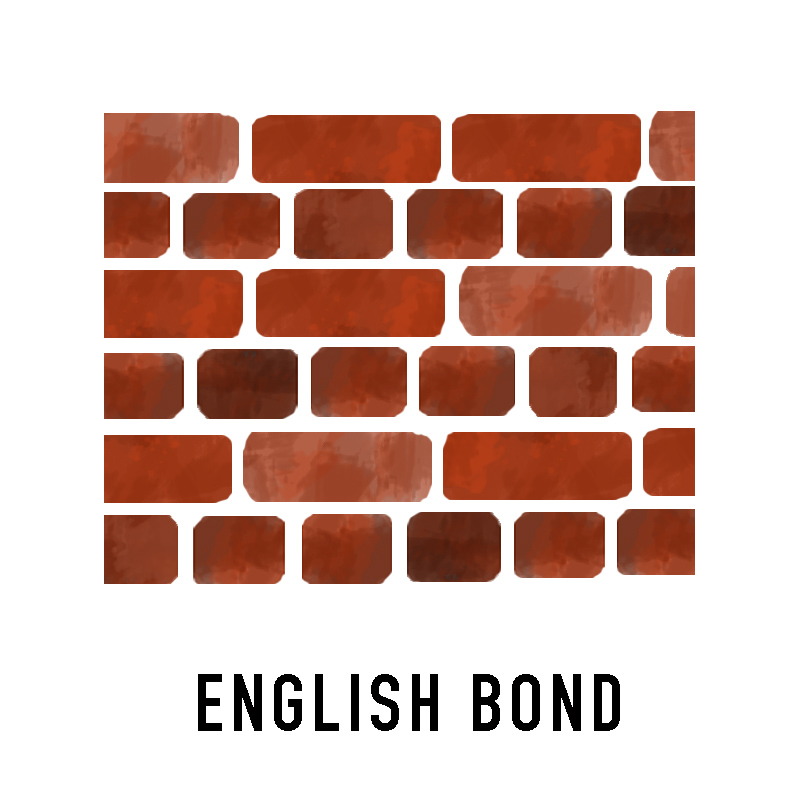

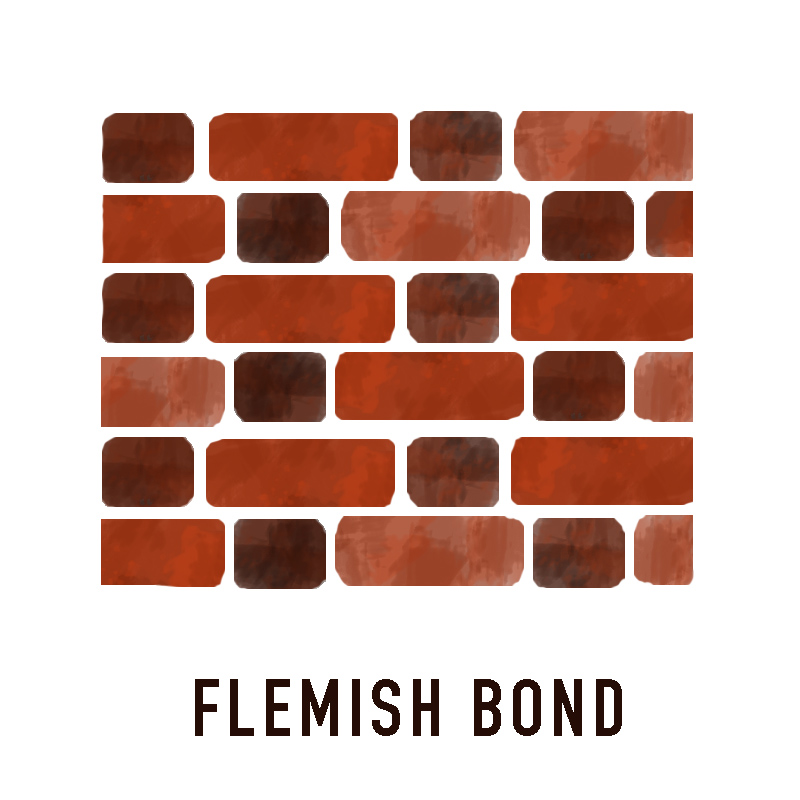

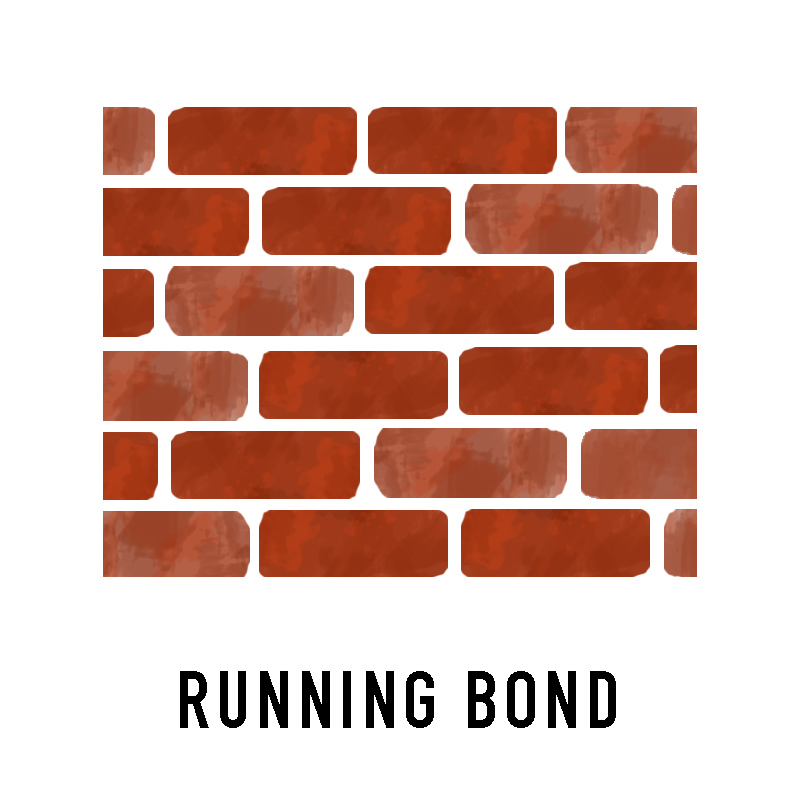

Although early row houses were half-timber, mimicking the English style, they soon switched to brick which was a better fire retardant. An abundance of local clay allowed brickmaking to flourish here. By the 18th century, we were America’s preeminent brickmaking city.

In the 19th Century row houses expanded into the Double Trinity or London House. These spacious 1,000-8,000 sq ft homes had three stories plus a basement, two fireplaces, and a rear yard. Today, these larger row houses ring Washington Square and may be found in several neighborhoods throughout the City.

The wealthy favored Townhouses, 3,000-7,000 sq ft with three to four stories, grand staircases, and abundant light. These are found in Society Hill and Washington Square West. A classic example is the Powel House, built in 1765 and located at 244 S. Third Street. It is now a museum and is considered to be one of the finest Georgian row houses in the city.

Row House Architectural Styles

Georgian houses, 1714-1830, featured symmetrical windows, shutters, and columns. Entrances were often embellished with pediments, arches, and columns. Interiors featured high ceilings and crown molding.

Federal style, 1780-1820, had many of the same elements but with details that are more delicate, including front door fanlight windows elaborate porticos, and curved arches.

Greek or Classical Revival started in 1820. The ceilings were taller. Attics were replaced by a full third floor. Examples include Girard Row, a set of five-row houses built in 1831 by banker Stephen Girard, located on the 300 block of Spruce Street. Or consider the elegant Thomas Eakins House, built in 1854, at 1727-29 Mount Vernon Street, now the headquarters of the Mural Arts Program.

Gothic Revival, 1830-1860, can be recognized by its pointed arches on roofs, windows, or doors. Other characteristic details include steeply pitched roofs and front-facing gables with delicate wooden trim called vergeboards or bargeboards. Examples can be found in West and North Philly. Tip: If it looks like the Adams Family lives there, it’s Gothic!

Renaissance Revival or Neo-Renaissance, 1840-1890, combined elements of Italian, French, and Flemish Renaissance architecture. They featured brownstone or light-colored brick facades and often had decorative motifs, like wreaths, and flower garlands along the cornice and around the windows.

Victorian style, 1837-1901, which often included Gothic elements, inspired the towering brownstone mansions found in Rittenhouse and Fitler Square. The 4100 block of Parkside Avenue in West Philly, built in 1876, during the Centennial Exhibition, is an excellent example of Gothic-Victorian style and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Mid to Late 19th Century

With the advent of the streetcar and increased immigration, developers expanded row house developments creating new neighborhoods close to factories and industry.

Small row houses with indoor plumbing, 1,000-1,600 sq ft, sprang up in Manayunk, as well as North, West, and South Philadelphia. Larger, “Streetcar Town Houses”, 2,200-2,500 sq ft, with front porches, bay windows, and tall ceilings also appeared in these areas.

For the elite, there were Urban Mansions, 3,00-6,000 sq ft with three to four floors, with two stairs (one for servants), carriage houses, skylights, and ornate fireplaces. In the 1890s, Urban Mansions attracted wealthy Jews to Strawberry Mansion in North Philly, while the City’s elite gravitated to Millionaires Row on South Broad. A beautiful example is the Lippincott Mansion, 1897, 507 S. Broad which featured a 10×20’ stained-glass skylight.

Our City’s row house styles are each unique in their right and built to last. From Kensington to East Passyunk, from West Philly to Germantown, these homes continue to stand the test of time, evolving and contributing to Philadelphia’s architectural landscape.

This article is part of a series titled “The Secret Life of Buildings” where we write about the history and architecture behind Philadelphia’s buildings. We’ve covered common Philadelphia brick styles, trinity homes, and star bolts, among other topics. What else would you like to learn about? Follow us and DM us on Facebook or Instagram to let us know!