architecture

How The Met in Philly Was Saved and Reborn as a Modern Concert Hall

The Met Interior. Image courtesy of Live Nation.

If ghosts lurk in any historic building, they most likely haunt The Met. No other structure has changed its identity as often and adapted to so many cultural, economic, and demographic shifts. We took a look back to see how many times The Met has fallen, only to rise again and again at 858 N. Broad Street,

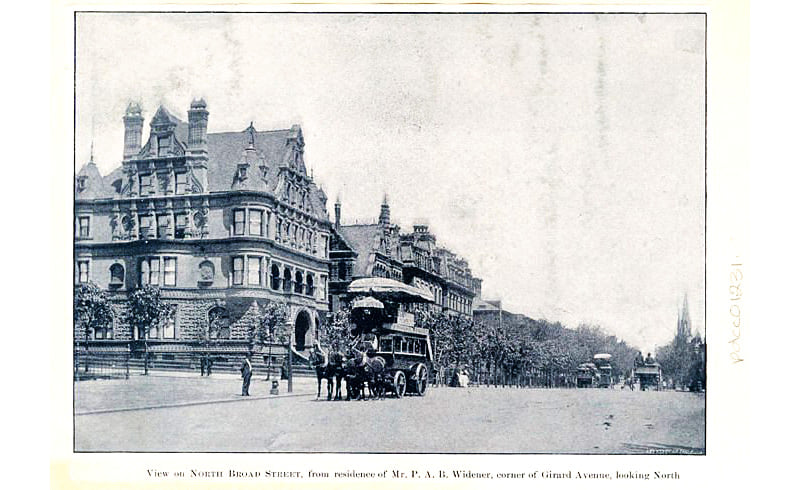

When the colossal Beaux Arts concert hall was first built in 1908 by New York impresario Oscar Hammerstein, he took a gamble, starting with a $400K loan from Philadelphia financier Edward T. Stotesbury. As an out-of-towner, as well as a German Jewish immigrant, Hammerstein misjudged the habits of Philadelphia’s elite. He selected a location at Broad and Popular, the former site of an industrialist’s mansion, as the permanent home for his Philadelphia Opera Company. His competition was the Academy of Music productions of New York’s Metropolitan Opera, which Hammerstein thought was inferior. Although Peter A. B. Weidner, one of the wealthiest men in the City, had a Gilded Age mansion at Broad & Girard, Blue Book Philadelphians considered it merely an upper-middle-class neighborhood of the nouveau riche.

By every measure, Hammerstein’s opera house was spectacular. It had 4,000 seats compared to the Academy’s 2,500, along with a double balcony, crystal chandeliers, and gold leaf-trimmed columns. Newspapers claimed it rivaled the grandest venue in Europe. In spite of sparing no expense on its productions, or maybe because of it, within just two years, financial problems forced Hammerstein to sell his opera house to his number one rival, the Metropolitan Opera, which is how it got the name that has stuck for over one hundred years. Ironically, the owner of the Metropolitan Opera was now Stokesbury. Hat in hand, Hammerstein sailed off to Paris and died five years later.

This wasn’t the end of The Met. In fact, it’s just the beginning. Blame it on Prohibition, but in 1920, Stokesbury auctioned off The Met, after which its fate moved faster than a three-card Monte game. First, it was a vaudeville venue, then a silent movie theater, and – for a head swiveling minute – it was the home of the Philadelphia Orchestra led by none other than Leopold Stokowski before being transformed into a basketball and circus venue. From 1939 to 1954, it was a boxing venue with a seating capacity of 5,500.

Then, The Met got religion. Purchased in 1955 for $250K by TV Evangelical preacher, Rev. Thea Felix Jones, it packed 5,000 worshipers into the theater every Sunday, plus thousands more in the television audience. Jones was born in Appalachia and had preached in tents, speaking in tongues, across the South before arriving in Philadelphia. Television preachers, including Billy Graham, were at their zenith. Although Jones claimed to restore sight to the blind and make the lame walk, his healing powers did not extend to The Met’s construction, which was falling apart. Rather than make any repairs, he relocated to a nearby church.

After Jones died in 1992, the City declared The Met unfit for occupancy. In 1996, the congregation, known as “Holy Ghost Headquarters,” purchased The Met for $250,000 to save it from demolition and spent $5 million in renovations in the early 2000s. Here is where it get murky. In 2012, developer Eric Blumenfeld, owner of the Divine Lorraine, acquired a controlling interest in the Met from the Holy Ghost Headquarters Church for just one dollar. At the time, Philadelphia Magazine called Blumenfeld “crazy” for casting his ambitions on North Broad Street. Who’s laughing now? Following Blumenfeld’s $58 million renovation project, he reopened The Met in 2018 as a 3,350-seat concert hall operated by Live Nation. He didn’t need a sound check. Hammerstein’s original efforts, a century before, to make the venue acoustically perfect, had not gone to waste. Back in the 1970s, recording engineers were so impressed with the sound quality of the Met, several albums of the Philadelphia Orchestra were recorded there.

Now, about those Holy Ghosts, the congregation retained 50% interest in The Met. Although they temporarily relocated to a Church during The Met’s renovation, they now hold services in Oscar Hammerstein’s lavish opera house. With current shows as diverse as Patti Smith, John Oliver, and Dancing with the Stars, plus boxing matches, the Met seems to have returned to its 1920s “something for everyone” appeal.

Ray Blau, an avid concertgoer whose taste runs from Bach to the Grateful Dead, was at the Met on opening night, December 2018, when Bob Dylan rocked the house. “I went to 23 concerts this year in various venues from New York City to Vegas,” said Blau. “The Met is fantastic!”