A new report from the Center City District reveals that downtown Philadelphia, long caught between the King of Prussia Mall and New York City, has emerged as a major upscale shopping destination, as retailers use the area’s population density to their advantage.

The Center City District’s annual retail report (seen in full here) features some truly impressive numbers: retail rents along the high-end Walnut Street shopping district have increased by 33.8% from 2012 to 2013, the strongest growth of any major urban retail corridor in the country.

Michelle Shannon, Vice President of Marketing and Communications for the Center City District, recently discussed this growth with Philly.com, saying that many now “feel like the rubber’s really hitting the road” for Center City retail investments and that “people we wouldn’t see four years ago, or signing leases in Philadelphia, are now open.”

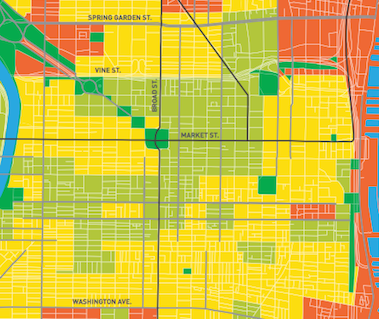

So what’s driving this growth? The report concludes Center City’s amazing density of jobs and residents is a key part of this success story. With over 100,000 residents in walking distance of major shopping streets, plus nearly nine times the office workers of King of Prussia, Center City retailers have easy access to customers.

In addition, this report reveals that district’s workers and residents are among the highest earning in the Philadelphia area as well, making Center City even more attractive to retailers.

Of course, as a city famous for its independent spirit, Philadelphians are sometimes wary of embracing the big national brands driving this retail renaissance. Boutiques and independent stores play a critical role in Center City’s retail market and still represent the majority of stores. Encouraging continued big developments, while also helping the city’s small businesses to share in that growth, is critical to ensuring a high quality of life (and sense of style) for Center City’s residents and workers.