Does your home have an intriguing history? Would you like to know who were its first tenants? If so, the City of Philadelphia makes it easy to trace your house’s past via maps and archival documents, including deeds that go back to 1683. Below is a list of local resources you can use to find more information about the history of your home.

Philadelphia City Archives

If your house was built prior to 1955, start with Philadelphia City Archives at 548 Spring Garden Street. There, archivists will conduct a detailed search for historical materials relating to the address you provide and present you with the appropriate files. You never know what you will find. The records may contain handwritten deeds, transfers of property, or architectural renderings. If you are a fan of Finding Your Roots, the PBS program that delves into genealogy, you will love the City Archives. To schedule a visit, call 215-685-9401.

Besides recording deeds, the City Archives maintains a Photo Archive of two million photographs, dating from the late 1800s, including images of the City’s architecture, industry, and culture. Tap into this fascinating resource to trace the changes in your neighborhood.

Philadelphia Department of Records

If your home was constructed between 1956 and the present, go to City Hall Dept. of Records. Since this office also contains records of births, deaths, and marriages, it may involve a longer wait than the City Archives. However, if you are nimble with technology, you can access digital property deeds online from 1683 through 1974 at the Philadelphia Dept of Records. Be prepared to buy a subscription to conduct a search and wade through a complex system of deed books.

These deed books provide a wealth of information regarding the ownership and use of real estate in Philadelphia. The standard deed includes information on the date of the transaction, the names, residences, and occupations of the buyer and seller, the sale price, a survey description of the property usually with an indication of whether there is a building on the property, a description, called a recital, of how the seller acquired the property.

Free Library Interactive Digital Mapping Tool

If you want to see how your block or neighborhood has changed over the years, the Free Library offers an interactive digital mapping tool, dating back as far as 1843. These are no ordinary maps! They include 19th-century maps of whiskey warehouses, Fairmount Park, horse car routes, and atlases of the City by wards.

Philadelphia Historic Commission

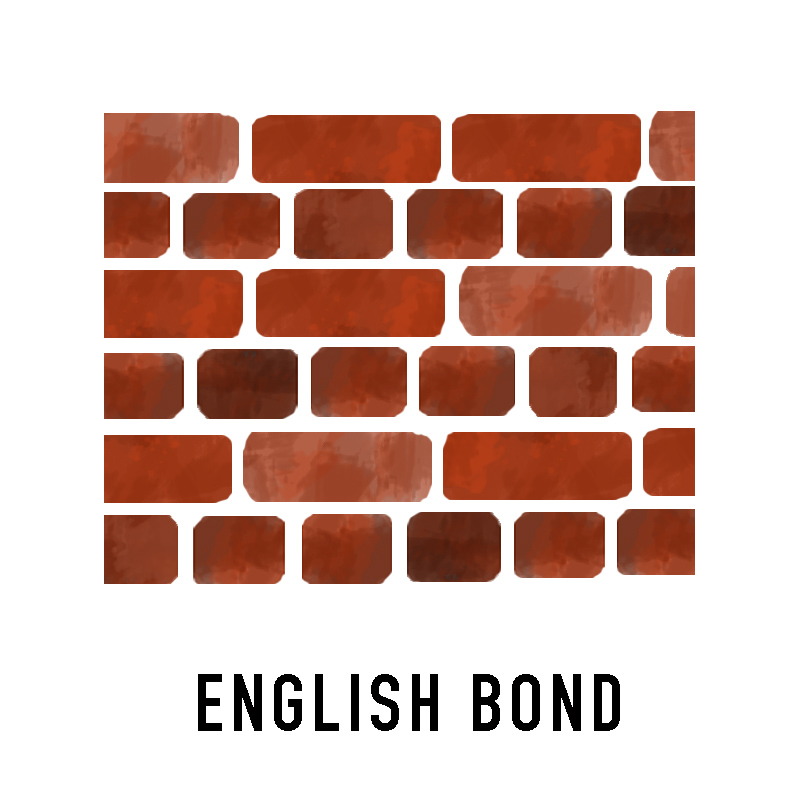

To find out if your property is registered as historic, to nominate a property, or apply for a historic plaque, contact the Philadelphia Historic Commission. Besides designating individual properties, the Commission also lists Historic Districts and offers manuals for homeowners in those neighborhoods. Besides the usual suspects, Philadelphia’s Historic Districts include West Girard Avenue, Diamond Street, Parkside, and many other architecturally significant areas.

Philadelphia Architects & Buildings

Philadelphia Architects & Buildings is also a helpful online tool to learn about the architect who designed your home. Hosted by the Atheneum, you simply enter the property’s address or the name of the architect. If there’s a match, you will have access to the architect’s resume, along with the locations of other properties he designed with dates and photos. To gain access without signing up for a subscription, sign in as a guest.

Whether you have an old home or are looking to purchase a new place to call home, researching the property’s history can be an important step in determining its value and preserving its architectural integrity.